Reel Horrors, Real Anxieties: An Interview with Dr. Meraj Mubarki

- Vinnie C

- Aug 11, 2025

- 6 min read

by Vinnie C and Sapna Moti Bhavnani

Most mornings, I start with the same ritual, coffee in hand, typing “horror in India” into the vast internet abys, only to be met with the usual uninspired mediocre headlines. But that morning was different. That’s when I found Dr. Mubarki. The thrill of it almost sent my coffee flying across the couch, and discovering how easy it was to reach him pushed that thrill into full-blown, out-loud screaming. It was the same rush I’d felt when I first came across Dr. Riksundar Banerjee, who’s since become a regular writer and was also a speaker at Wench Film Festival 2025.

Talking to Dr.Mubarki felt less like an interview and more like stepping into a haunted labyrinth, each turn revealing another hidden chamber of Indian horror cinema. Just when you think you’ve hit the heart of the genre, it twists again, unearthing new layers of myth, memory, politics, and desire. With sharp clarity and a touch of wit, Dr. Mubarki doesn’t just explain horror, he lets it haunt the conversation, showing how deeply it's stitched into our films and fears.

Dr. Meraj Ahmed Mubarki doesn’t just watch horror films, he anatomizes them. With the precision of a scalpel, he slices through the flesh of Indian horror cinema to reveal the pulsating anxieties underneath. A scholar with an eye for rot and subtext, Dr. Mubarki is one of the few voices treating Indian horror with both reverence and irreverence, exactly what the genre demands. His forthcoming Routledge title “Mythic and Monstrous” is primed to do what most critics won’t: take horror seriously, grime and all.

His earliest encounters with horror didn’t come via footnotes and film theory, but through bloodlines. Growing up on a steady stream of cinematic chills, thanks to a father who was knee-deep in the Bengali film distribution circuit, Dr. Mubarki was introduced to The Exorcist (1973) and Poltergeist (1982) long before peer-reviewed journals. Horror, in his world, was not an acquired taste, it was an inheritance. By the time he entered academia, he was already fluent in dread.

His first book, published by Sage, carved a path through Hindi horror’s rocky terrain, framing the genre through gender, power, and performance. Where others dismissed, he dissected.

For Dr. Mubarki, the ghost on screen is never just a ghost. It's a class struggle in makeup. It’s sexual repression with a smoke machine. Take Madhumati (1958): often viewed as a romantic thriller, he sees it as a ghost story rooted in post-Independence optimism. “A ghost seeking justice from the police,” he quipped. “That’s Nehruvian hope for you, trusting the police.” Even before Indian cinema had an official horror genre, it had ghosts working overtime as metaphors.

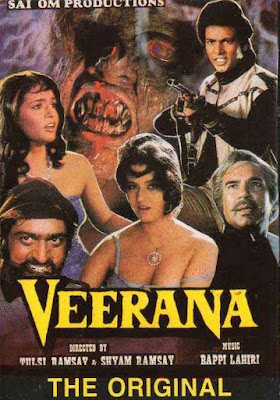

In the 50s and 60s, the genre dealt in whispers, not screams. Films like Bees Saal Baad (1962) and Woh Kaun Thi? (1964) leaned into psychological thrills, madness, memory, and mystery. But by the 80s, horror had gone full technicolor. Gone were the subtle shadows; in came the sex, the gore, and the Ramsay Brothers. Lower the ticket price, skip the maintenance, and what do you get? Single-screen audiences full of young men chasing cheap thrills, he explained. And the Ramsays delivered: dismembered limbs, bare midriffs, and plotlines stitched together with fake blood and ambition.

But horror, like India itself, liberalized. The 90s ushered in middle-class decency and internet porn. Horror had to clean up its act, swap lingerie for lighting design. Films like Raat signaled the shift: moody, restrained, and noticeably more clothed. Horror had to wear a shirt.

Zombies? Don’t hold your breath. As he pointed out, “You need a graveyard for zombies. Hindu rites do away with the body.” In Indian horror, even the undead struggle with infrastructure.

What sets Dr. Mubarki’s scholarship apart is how keenly he reads the genre through the female body as well. Indian horror, he argues, is obsessed with women who transgress. Too sexual, too independent, too alive. They’re promptly turned into ghosts. In Veerana (1988), the spirit is overt in her seduction. In MangalSutra (1981), a woman dares to desire a married man and is punished for it. “The blame is always hers,” he notes. Never the man’s for getting seduced in record time.

And then, there are the queer phantoms. Consider Rekha’s husband, possessed by a woman in Khoon Bhari Maang (1988): when he assaults her, who is really responsible? It’s the beginning of Bollywood’s demonisation of queerness; tracing a line through Laxmii (2020).

Then there’s Tumbbad (2018), an outlier, a masterpiece. It’s grotesque and mythic. Cronenberg meets Marathi folklore. It’s not just fear; it’s inheritance, hunger, rot passed down like heirlooms.

Compare that with Stree (2018) and its sequel. The original, he says, was smart, subversive. A chudail that hunts men, that’s a delicious flip. The follow-up? “Franchise logic took over. They threw everything in. It’s not horror anymore. It’s horror-adjacent masala.” And the ghost? A bride with nowhere to go, so she takes your man. Textbook anxiety.

But horror, he insists, is cyclical. “It collapses. Then reinvents. Always.” Today’s horror straddles extremes. It’s being turned into a comedy for mass appeal. But it’s also being taken seriously in indie spaces and streaming platforms. In Bulbbul (2020), the ghost is not evil, she’s emancipated. Pari (2018) flirts with divinity and dread.

And what scares the scholar himself? Not much. Jump scares? Child’s play. It’s dread that’s hard to pull off. “Raat (1992) did it. It frightened by the suggestion. Not sound design.” The real art lies in holding unease, not detonating it.

Ask him for a double feature and he doesn’t hesitate: The Exorcist (1973) and Evil Dead (1981). “One is sacred. The other is trash. But both get transformation. And that’s horror.”

That’s also Dr. Meraj Ahmed Mubarki. A man who sees ghosts not just as cinematic devices, but as cultural diagnostics. Through his lens, horror isn’t just what we fear, it’s what we repress, deny, and bury. Until it comes clawing back.

Learn more about Dr. Mubarki

Dr. Meraj Ahmed Mubarki is an Associate Professor at the Department of Mass Communication and Journalism, Maulana Azad National Urdu University, Hyderabad. With a Ph.D. in Journalism and Mass Communication from the University of Calcutta, his work spans film theory, media and cultural studies, and gender in cinema, particularly Hindi horror. He is the author of “Filming Horror” (SAGE, 2016) and the forthcoming “The Horror in Hindi Cinema: Between the Mythic and the Monstrous” (Routledge, 2025). His research has appeared in leading journals like Contemporary South Asia, Indian Journal of Gender Studies, and Visual Anthropology, and is cited in university curricula worldwide. A former National Film Archives of India Fellow, Dr. Mubarki is recognized for his sharp insights into the ideological undercurrents of Indian cinema.

Buy Dr. Mubarki's books here 👇

Read more of Dr. Mubarki's work here 👇

1. 2022 Nip, snick, cut! Decoding film censorship in India 1920-1928. Feminist Media Studies.

Published online: 26 Oct 2022. Impact Factor: 3.290 (2021) 5-year IF

and Video. 38 (2). 91-115.

Social Semiotics, 30 (2), 274-302. Impact Factor: 1.16 (2019)

Cinema. South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, XLI(4), 723-743. Impact Factor:

0.394 (2019)

5. 2018 Body, masculinity and the male hero in Hindi cinema. Social Semiotics, 30(2), 225-

253.

Impact Factor: 1.16 (2019)

Cinema. Visual Anthropology, 30(1), 45-64.

Hindi cinema. Contemporary South Asia, 24(2), 164-183.

Visual Anthropology, 28(3), 248-261.

Cinema. Indian Journal of Gender Studies, 28(3), 248-261. Impact Factor: 0.195

10. 2014 Exploring the 'Other': Inter faith marriages in Jodhaa Akbar and beyond. Contemporary South Asia, 22(3), 255-264.

Sociology of South Asia, 7(1), 39-60.

12. 2012 Sexual Content in Indian TV commercials. Media Asia, 10 (1), 191-198.

Comments